Un même poisson à quelques neurones hypocrétinergiques près par Contributeur 12.03.2018 à 09h37

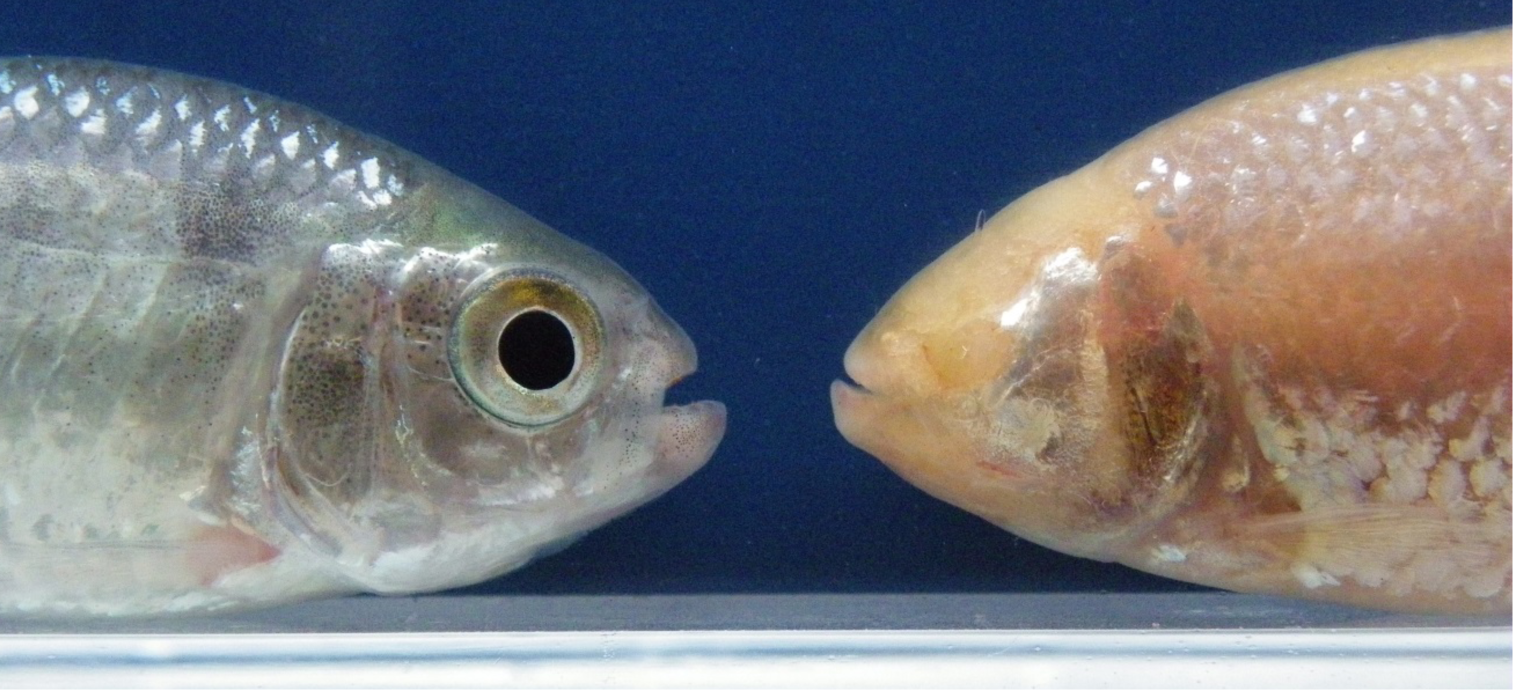

L’un est coloré et vit dans les rivières d’Amérique latine, l’autre est aveugle, dépigmenté et habite dans l’obscurité des grottes mexicaines, pourtant ce sont les mêmes poissons : Astyanax mexicanus. Des chercheurs de l’Institut des neurosciences Paris-Saclay (CNRS/Université Paris-Sud) ont recherché les mécanismes embryonnaires à l’origine de leurs différences morphologiques et comportementales.

Comment les spécimens cavernicoles ont-ils évolué afin de survivre dans un tel environnement ?

L’évolution du développement cérébral et ses conséquences comportementales est un sujet majeur pour comprendre comment les vertébrés colonisent les environnements nouveaux. Astyanax mexicanus est un modèle de choix pour aborder cette question.

Ce poisson présente deux morphotypes: une forme d’habitat de surface qui habite les rivières de l’Amérique Centrale et du Sud, et une forme cavernicole composée de plusieurs populations vivant dans l’obscurité totale et permanente des grottes mexicaines.

Les poissons cavernicoles ont évolué vers des traits régressifs – les plus spectaculaires étant la perte des yeux et de la pigmentation – mais ils ont aussi développé plusieurs traits constructifs tels qu’une mâchoire plus large, plus de papilles gustatives, ou des épithéliums olfactifs plus importants, et aussi de nombreux changement comportementaux. Parmi les plus frappants : les morphes cavernicoles dorment très peu et nagent en permanence.

Les chercheurs de l’Institut des Neurosciences Paris-Saclay (CNRS/Université Paris-Sud) ont observé qu’un nombre différent de certains neurones se développait dans l’hypothalamus chez les embryons des deux spécimens. Cette variation naturelle dans le développement cérébral impacte non seulement la morphologie des poissons cavernicoles mais aussi leur comportement.

En intervenant sur le développement neuronal des larves du poisson cavernicole, les chercheurs sont parvenus à leur faire mimer le comportement du poisson de surface. Ce travail révèle donc de nouvelles variations sous-jacentes à l’évolution et à l’adaptation des poissons cavernicoles à leur environnement extrême. Ces variations en nombres de neurones trouvent leur origine dans des processus embryonnaires très précoces, qui se produisent pendant les dix premières heures après la fécondation, lorsque l’embryon n’est encore qu’une « boule de cellules ».

Références :

Developmental evolution of the forebrain in cavefish, from natural variations in neuropeptides to behavior, Alexandre Alié, Lucie Devos, Jorge Torres-Paz, Lise Prunier, Fanny Boulet, Maryline Blin, Yannick Elipot et Sylvie Rétaux, eLife, 6 février 2018. doi.org/10.7554/eLife.32808

Contact chercheur:

Sylvie Rétaux

Institut des Neurosciences Paris-Saclay

Développement & Évolution du cerveau antérieur

retaux@inaf.cnrs-gif.fr

The same fish but a few more Hypocretin neurons

New insight into the development and function of Mexican cavefish brains reveals how the animals adapted their behaviour to cope with extreme environments.

There are two forms of A. mexicanus: surface-dwelling fish that inhabit rivers in south and Central America, and fish that live in the total and permanent darkness of Mexican caves. The cavefish display striking differences from their river-dwelling counterparts, including the loss of sleep that makes them a potential model to study human sleep disorders such as insomnia.

In a study published in eLife, researchers from the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) and Université Paris-Saclay demonstrate how the developmental evolution of the brain in cave-dwelling Astyanax mexicanus (A. mexicanus) underlies the evolution of its survival behaviors. A second study from the US, published at the same time in eLife, suggests higher levels of hypocretin (HCRT) in the cavefish brain – a chemical compound associated with human narcolepsy – accounts for the loss of sleep in these animals.

“A. mexicanus cave-dwellers have developed this and other beneficial behaviors that allow them to live in adverse environments,” says senior author Sylvie Rétaux, Group Leader at CNRS, Paris-Saclay Institute of Neuroscience. “This makes them a prime model to study the evolution of brain development and its behavioral consequences, providing greater understanding of how vertebrates colonize more unusual locations.”

In their study, Rétaux and her team compared the development and natural variations of anatomy in the brains of both surface and cave-dwelling A. mexicanus embryos and larvae, highlighting specific differences in the numbers of neurons between the two forms. “We discovered a higher number of HCRT cells developing in the brains of cave-dwelling fish compared to surface-dwellers,” explains postdoctoral researcher Alexandre Alié. “By manipulating the numbers of HCRT neurons, we were able to link these to increased activity levels in the animals.” Jorge Torres-Paz, also a postdoctoral researcher at CNRS, adds: “Interestingly, we found that the variation in HCRT neuron numbers stems from very early embryonic events, which occur as early as within the first 10 hours after fertilization, when the embryo is still like a ball of cells. This suggests the mechanisms that lead to the loss of eyes could be shared in part with those that control developmental evolution of brain and behaviour, including sleep.”

These findings show that developmental evolution of the cavefish brain drives evolution in the animals’ behavior. More generally, they also support a role for HCRT in relation to sleep in other animals, providing a new system for investigating sleep differences throughout the entire animal kingdom.